Bow

Down to Her on Sunday

Bow

Down to Her on Sunday

by John Gibbens

This article first appeared in Judas! magazine.

Among the reviews

of The Nightingale’s Code, my ‘poetic study’ published

by Touched Press in October 2001, one common note was sounded. Whether

the reviewer was appreciative (Paula Radice in Freewheelin’),

dubious (Jim Gillan in Isis) or dismissive (Nigel Williamson in

Uncut), the same point got picked on by each of them to demonstrate

my occasionally – some said, and some said chronically – wayward

thinking. This egregious fallacy was my suggestion that ‘To Ramona’,

in its title, refers to the Tarot, and in particular to two cards, the

High Priestess and the Wheel of Fortune. I’ll restate my case in

a moment. Here is how Paula Radice responded to it: ”I can accept…

Gibbens’s view that the cycle of the first seven albums (up to the

‘cycle’ accident!) turns around a midpoint of ‘To Ramona’

on Another Side of Bob Dylan. … Where Gibbens loses me is

then putting forward, as part of the justification for this thesis, that

the first part of the title – To Ra – means Tora, the Tarot,

and the Latin rota or ‘wheel’, and that these were deliberate

inferences on Dylan’s part. It just seems unnecessary, indeed counter-productive…”

And this was Nigel Williamson’s view: “… if you didn’t see the significance in the fact that the first four letters of the title ‘To Ramona’ spell TORA, which is the word on the scroll held by the High Priestess in the Tarot pack, then your appreciation of Dylan is superficial indeed. You’re probably the sort of person who doesn’t even appreciate that his early lyrics are characterised by the use of the metrical foot known as the anaepest. [sic]” This is mere misrepresentation. I do not imply – certainly not in the section under discussion here, and I hope nowhere else – that someone’s listening which is not informed by the circumstances or connections I fetch to a song, whether from far or near, is therefore shallow or wrong or inadequate. If I propose a thought you had not already had, or convey some fact you didn’t know, am I thereby calling you ignorant? No: though not being able to copy the correct spelling of a word – like ‘anapæst’, say – from a book you are reviewing could be considered ignorant.

Never

mind. For now, I’m interested in why this ‘To Ra’ idea

of mine caught the flak. But first let me explain it a bit more. My argument

seems not to have been clear in the book, since none of the three reviews

I’ve mentioned restated quite what I thought I had proposed. I’m

not suggesting that Dylan juggled the four letters TORA to get Tarot and

also ‘rota’, the Latin wheel, or that he would ever expect anyone

to follow such a leap if he had made it. The letters appear like this,

‘TORA’, on the High Priestess card, and they also appear at

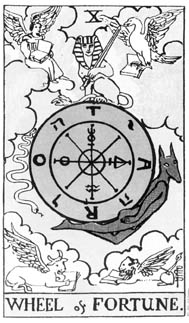

the four cardinal points around the Wheel of Fortune, as T–A–R–O,

just as N, E, S, W appear on a compass. But Dylan did not need to connect

these himself – the link is made by A.E. Waite, who designed the

pack in question, in his accompanying book The Key to the Tarot.

He points out the letters and explains that they can be read clockwise

from T in the ‘North’ position, back to T again, to spell ‘Tarot’;

or from R in the South, clockwise, to read ‘Rota’; or from the

T, anticlockwise, as far round as A, to read Tora. He further points out

that this is the word on the High Priestess’s scroll, and that it

stands for Torah, which is the Hebrew for law, or instruction, or direction,

and the name given to the first five books of the Bible.

Never

mind. For now, I’m interested in why this ‘To Ra’ idea

of mine caught the flak. But first let me explain it a bit more. My argument

seems not to have been clear in the book, since none of the three reviews

I’ve mentioned restated quite what I thought I had proposed. I’m

not suggesting that Dylan juggled the four letters TORA to get Tarot and

also ‘rota’, the Latin wheel, or that he would ever expect anyone

to follow such a leap if he had made it. The letters appear like this,

‘TORA’, on the High Priestess card, and they also appear at

the four cardinal points around the Wheel of Fortune, as T–A–R–O,

just as N, E, S, W appear on a compass. But Dylan did not need to connect

these himself – the link is made by A.E. Waite, who designed the

pack in question, in his accompanying book The Key to the Tarot.

He points out the letters and explains that they can be read clockwise

from T in the ‘North’ position, back to T again, to spell ‘Tarot’;

or from R in the South, clockwise, to read ‘Rota’; or from the

T, anticlockwise, as far round as A, to read Tora. He further points out

that this is the word on the High Priestess’s scroll, and that it

stands for Torah, which is the Hebrew for law, or instruction, or direction,

and the name given to the first five books of the Bible.

Before we go any further, there are a few supporting points I should make. First, these writings of A.E. Waite are not at all obscure or esoteric. The Waite pack is probably the most popular form of the Tarot to this day, and would have been by far the most likely pack you’d come across in 1964, back before the general revival of the ‘occult’ led to a profusion of new designs. Likewise, Waite’s book is one of the favourite beginner’s guides to the cards and has been reprinted many times. I bought it as a cheap, recently published paperback in the 1980s.

Second, we know that, many years later, Dylan took an interest in the Tarot and the Waite pack in particular. He ‘quotes’ the Empress card from it on the back sleeve of Desire. Even from a cursory look at the symbols and the ways of interpreting them, the influence of cartomancy – and especially the kind of symbolism that Waite draws from, mixing the biblical with the magical – can be seen both in Street-Legal and Renaldo & Clara. In the film, when Joan Baez appears as the Woman in White clutching a red rose, she echoes both the Empress, who wears a white gown sprigged with red roses, and the High Priestess herself, who wears a blue mantle over what I take to be a shimmering white gown. (It’s coloured white in places and blue in others – I think to give a moonlit effect. She has the full moon set in her crown and the crescent moon at her feet, and sits as it were in an alcove between two pillars, one black and one white.)

In

Waite’s little instruction pamphlet that comes in the box with the

cards, the High Priestess is said to represent, in a reading, “the

woman who interests the Querent, if male; the Querent herself, if female”.

She also stands for “silence, tenacity, mystery, wisdom”. (Which

is about as much detail as any of the biographers have been able to disclose

about the character of Sara Dylan, isn’t it?) For all her virginal

and remote attributes, it’s the Priestess and not, for example, the

much more ‘earthy’ seeming Empress, who signifies a sexual and

romantic relationship with a woman.

In

Waite’s little instruction pamphlet that comes in the box with the

cards, the High Priestess is said to represent, in a reading, “the

woman who interests the Querent, if male; the Querent herself, if female”.

She also stands for “silence, tenacity, mystery, wisdom”. (Which

is about as much detail as any of the biographers have been able to disclose

about the character of Sara Dylan, isn’t it?) For all her virginal

and remote attributes, it’s the Priestess and not, for example, the

much more ‘earthy’ seeming Empress, who signifies a sexual and

romantic relationship with a woman.

Now perhaps we can see a link between the High Priestess and ‘To Ramona’, with its peculiar blend of ‘high’ philosophising and sensual romancing. It doesn’t seem to me far-fetched to suggest that the song arises from the combination of experience and meditation on this image. It’s interesting that ‘Torah’ should mean instruction or direction, given that the song mixes several direct instructions – “come closer, shut softly your watery eyes” – with its more abstract teachings – “Everything passes, everything changes” and so on.

Here I should make a third substantiating point. This stuff about the Tarot may or may not interest you, but I think you’ll agree that it is directly relevant to one period of Dylan’s work at least; that he clearly had its symbolism in mind about the time of Street-Legal and Renaldo & Clara, and that he invites us, as openly as he has ever done with any outside source, apart from the Bible, to use the Tarot as a ‘key’ to some of his images. But that was then. Is it likely that he’d known about, let alone thought about the cards, and used their symbolism as a source for his art as early as the mid-1960s?

Well,

the biographical evidence suggests that he learned about the Tarot from

Sara, whom he most likely met sometime in 1964. Now here’s a nice

piece of circumstantial evidence. The cover photograph of Bringing

It All Back Home was taken in the first weeks of 1965. Put the Empress

on the back cover of Desire alongside Sally Grossman, the lady

in red on the front of BIABH (much easier to see if you’ve

got the LPs). Do my eyes deceive me, or is that almost the same pose?

Well,

the biographical evidence suggests that he learned about the Tarot from

Sara, whom he most likely met sometime in 1964. Now here’s a nice

piece of circumstantial evidence. The cover photograph of Bringing

It All Back Home was taken in the first weeks of 1965. Put the Empress

on the back cover of Desire alongside Sally Grossman, the lady

in red on the front of BIABH (much easier to see if you’ve

got the LPs). Do my eyes deceive me, or is that almost the same pose?

I hope I’ve made a case, at least, that Dylan’s quite deep knowledge of the Tarot could go back a long way before Renaldo & Clara. While I’m making this defence, I’d like to make a retraction too. In my book I claimed of the Dylans, “We can date their meeting fairly accurately”. This was showing off, because I was pleased with myself for having tracked down two decaying hurricanes that hit New York in the autumn of 1964 – on 14th and 24th September – and concluded that this must pinpoint the “tropical storm” that is mentioned in the song ‘Sara’ as marking their meeting. They were the only truly tropical storms to reach the northeastern seaboard that season, but it’s still just a guess, and a far cry from “fairly accurate” dating.

I’d much rather, really, that they’d met a lot earlier, before 9th June 1964, for example, when Another Side was recorded. Then maybe that storm could be the tremendous one of ‘Chimes of Freedom’, and they could be that “we”: “Starry-eyed and laughing as I recall when we were caught, / Trapped by no track of hours…” The ‘message’ of ‘Chimes of Freedom’, with its Sermon on the Mount echoes, also chimes with that line in ‘Sara’ – “A messenger sent me in a tropical storm.” (The sentence is ambiguous: he was sent along by the messenger is the top meaning; but it can be read grammatically as “How did I meet you? … [By means of] a messenger sent [to] me in a tropical storm.”)

If a ‘real-life’ Ramona is required, Sara is a much more natural one than, say, Joan Baez. The Tarot doesn’t seem like Joanie’s bag, and nor do the confusion and tears that Ramona shows. But the feeling of being torn that the song describes wouldn’t be surprising in a woman, like Sara at that time, with a young child and a marriage falling apart.

Identifying Sara, or anyone else, with Ramona doesn’t tell us much about the song (though the song might tell us something biographically about a relationship). But associating Ramona with the High Priestess, it seems to me, does add something to the song. It strengthens our sense of Ramona’s dignity – “the strength of your skin”, those “magnetic movements” – that counterbalances this temporary bewilderment and weakness. It heightens the feeling of reciprocity. If Ramona is, in her better self, like the Priestess, then she is herself the source of wisdom and knowledge, and this situation where the singer is spelling out the facts of life for her could as easily be reversed, as the last lines acknowledge: “And someday, baby, / Who knows, maybe / I’ll come and be crying to you.”

As the precursor to a string of notable ‘advice-to-a-woman’ songs – ‘It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue’, ‘Like a Rolling Stone’, ‘Queen Jane Approximately’ – the Priestess image reinforces a basic respect that underlies them, that keeps them, somehow, despite their outspokenness, from sounding merely gloating or contemptuous. Much has been said of the viciousness, the sneer, the anger of ‘Like a Rolling Stone’, but what has kept it alive so long is the way that this is mixed with a kind of stateliness. And this stateliness pertains to the person that the song describes, just as it does in ‘Queen Jane’. We may see the women, in the images, stripped of their trappings of comfort, prestige and power, but in the music we see them somehow the stronger for it. What makes the songs moving and lasting is the feeling that Dylan conveys, in everything apart from the words, that he’s not crowing ‘I told you so’, but saying rather, as he says Ramona says, “You’re better than no-one / And no-one is better than you.” That is a philosophical constant of Dylan’s work, a ‘something understood’ that keeps him on a level with us, however ostensibly preaching or haranguing or even vituperative his words. And this is what enables them effectively to preach and teach.

My

reason for mentioning the ‘To Ra’ hypothesis in The Nightingale’s

Code was not so much to do with the High Priestess as with the Wheel,

the Rota. Of course, this period of Dylan’s life was a ‘turning

point’. What intrigued me was how consciously he seems to have realised

it. The image of a wheel or ring is deliberately evoked in the front of

Bringing It All Back Home, and it occurs in that key song ‘Mr

Tambourine Man’, in the tambourine itself and in the “smoke-rings”

of the mind, and also in ‘To Ramona’: “my words would turn

into a meaningless ring… Everything passes, everything changes”.

I go on to discuss how Another Side itself seems to rotate around

this central point, ‘To Ramona’, turning from a positive first

side – Incident, Freedom, Free, Really – to a negative second

– Don’t, Ain’t, Plain, Nitemare and so on; turning right

round, in the end, from “All I really want to do is, baby, be friends

with you” to “It ain’t me you’re lookin’ for,

babe.” From there I go on to suggest an even wider wheel, still centred

on ‘To Ramona’, with the three folk albums on one side and the

three rock albums on the other. And there I leave you to decide for yourselves

with what kind of consciousness Dylan could have created the ‘centre’

of such a wheel, when he could not know where it would stop.

My

reason for mentioning the ‘To Ra’ hypothesis in The Nightingale’s

Code was not so much to do with the High Priestess as with the Wheel,

the Rota. Of course, this period of Dylan’s life was a ‘turning

point’. What intrigued me was how consciously he seems to have realised

it. The image of a wheel or ring is deliberately evoked in the front of

Bringing It All Back Home, and it occurs in that key song ‘Mr

Tambourine Man’, in the tambourine itself and in the “smoke-rings”

of the mind, and also in ‘To Ramona’: “my words would turn

into a meaningless ring… Everything passes, everything changes”.

I go on to discuss how Another Side itself seems to rotate around

this central point, ‘To Ramona’, turning from a positive first

side – Incident, Freedom, Free, Really – to a negative second

– Don’t, Ain’t, Plain, Nitemare and so on; turning right

round, in the end, from “All I really want to do is, baby, be friends

with you” to “It ain’t me you’re lookin’ for,

babe.” From there I go on to suggest an even wider wheel, still centred

on ‘To Ramona’, with the three folk albums on one side and the

three rock albums on the other. And there I leave you to decide for yourselves

with what kind of consciousness Dylan could have created the ‘centre’

of such a wheel, when he could not know where it would stop.

Which brings me back to my original question, why the reference to such esoterica as the Tarot got picked up. If there is any substance to my idea of a larger organised form to the whole sequence of Dylan’s first seven records, then how did it get organised? It suggests a shaping power of imagination far beyond what the ordinary Selfhood could encompass.

* * * * *

The Canadian critic Northrop Frye wrote in Fearful Symmetry, his inspiring study of William Blake, “If a man of genius spends all his life perfecting works of art, it is hardly far-fetched to see his life’s work as itself a larger work of art with everything he produced integral to it”. This idea he expanded further in Anatomy of Criticism, which might flippantly be called the prequel to Fearful Symmetry, since it outlines the vision of all literature which he had seen through his reading of Blake: “It is clear that criticism cannot be a systematic study unless there is a quality in literature which enables it to be so. We have to adopt the hypothesis, then, that just as there is an order of nature behind the natural sciences, so literature is not a piled aggregate of ‘works’, but an order of words.”

My aim in The Nightingale’s Code was simply to set such a vision of Dylan’s work afoot. To be honest – not wanting to launch an anti-advertising campaign – this was what I’d missed in the critical studies I’ve read. The observations accumulate but they don’t seem to assemble into a picture. It’s not clear what the details are details of. I wanted to show how, for example, song might relate to song on an LP; how LPs themselves might be constellated in phases or cycles – or chapters, if you like. Also, what might be constants of the whole work, the forms and images that speak to each other across it. In this I seem so far to have failed, since the critic who was most responsive to the book, Paula Radice, took exception to precisely this schematic aspect of it.

The tenor of most Dylan criticism at the moment is to celebrate the diversity of his work – to multiply its breadth and open-endedness. At the same time, I believe the perception that Dylan’s work is a whole, even while it can’t yet be seen whole, is well established. Many people – I would guess it’s probably most of the people who enjoy his music – have the sense that it’s worth getting to know extensively. There may be a certain consensus on the highs and lows, as well as our own personal charts, but I think most of us feel that the body of work adds up to something more than a selection of its highlights, however collectively edited. Don’t you also find yourself drawn back more often, and getting more out of a Dylan record you regard as second-rate than many a first-rate record by other artists?

Of course there are two important obstacles to studying Dylan as Frye studied Blake. One is that he is alive, and we can’t claim to see the work whole while it is still unfinished. The other is that it’s not literature. What constitutes the canon of Dylan’s work? ‘Mr Tambourine Man’, say, is an element of it, but what is ‘Mr Tambourine Man’? The first track on Side 2 of Bringing It All Back Home, or any one of the hundreds of other performances by Dylan himself, or for that matter by anyone else? In my book I opt for the official releases as forming a canon within the canon, so to speak. The artist himself gives some warrant for this. He doesn’t as a general rule give his songs in concert until they’re out on record – so that the live versions must to some extent be heard as subsequent variants of an original.

The profusion of variants with Dylan has no real parallel among the poets of literature, but it’s not an alien thing altogether. The canons of poets are mostly synthetic; few are crystalline, fixed and simple. ‘A’ poem is often surrounded by a penumbra of other versions, earlier forms and later revisions. The ‘death-bed collected’ is the usual basis of a canon: the poems, and the forms of them, that were last authorised by the poet in their lifetime. But this needn’t prevail. Whitman, Wordsworth and Auden, for example, are all felt to have done injustice to their early work with later changes, and so there is often an alternative version of the poems as they first appeared.

The canon of William Blake is, in fact, a striking anomaly something like Dylan’s. Not because Blake showed uncertainty in constituting his works: of him, more than any other English poet, we can say that the canon is ‘writ in stone’, since he personally, laboriously engraved in copper every single letter and punctuation mark of his completed poems. But the works he conceived are unities of word and image, and each copy of one of his Prophetic Books is unique, a combination of printing and painting. If he had had the audience and the resources, there might be as many Miltons and Jerusalems as there are ‘Mr Tambourine Men’. Well, almost. So the words of one of the poems reprinted in a book are not the actual thing that Blake made. This is why his work, though its influence grows year by year, is still regarded as obscure: because it is, and will be until there is a permanent free public exhibition of all his illuminated books together. At least there is, at last, two centuries on, an affordable one-volume, full-size reproduction (The Complete Illuminated Books, Thames & Hudson, 2000).

For future generations, the canon of Dylan’s work will pretty certainly include the concert recordings, studio outtakes and so on which are currently collected and curated by the fans. This is a fittingly democratic way for it to form, outside the ambit of the academies which Dylan has often berated. But I predict that the official albums will be the central structure around which the rest is organised, and I think that Dylan appreciates this, despite his pronouncements in periods of discouragement that he didn’t really care about making records, so long as he could perform. This was when he didn’t particularly care about making new songs either: compare and contrast with the clear sense of achievement that comes through in interviews now at having made “a great album” in Love and Theft.

In an album, a set of songs is organised into a greater whole; in a concert they are organised into another, different whole. ‘Sugar Baby’ belongs at the end of Love and Theft; in a concert we might discover that it also belongs perfectly between ‘Buckets of Rain’, say, and ‘It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue’. This independence of the songs, their constant movement in relation to each other, does not diminish the order of the canon, but serves to knot it all the more integrally together. It may seem to have no parallel with the way that poems appear in a poet’s book, always the same words on the same page. Yet what Dylan does for us with his songs is quite close to the way that poets begin to be read when we know them well enough, so we can turn from one poem to another, cross refer, even read two poems side by side, nearly simultaneously.

When I called my book The Nightingale’s Code I was obviously playing on the idea that Dylan is an enigma – that Dylanologists are still engaged in trying to ‘decode’ his lyrics. But I meant it more seriously in the sense of a ‘code of behaviour’, like the “code of the road”. The word comes from the Latin codex, which means originally a block of wood. A block was split to form leaves on which to engrave important and permanent documents, such as laws. In English the word ‘code’ – before it became synonymous with ‘cipher’ – meant “a digest of the laws of a country, or of those relating to any subject” and “a collection of writings forming a book” (Oxford English Dictionary). In other words, it’s an alternative term for the ‘canon’ that I’ve been using here. To my mind, the ‘code’ in Dylan – in the secret-language sense – is simply his ‘code’ in this second sense: the integrated body of work in terms of which each part can be interpreted.

The resistance to my ‘To Ra’ idea – an arcane reference couched in a form rather like a cryptic crossword clue – springs I think from a generally healthy scepticism about hidden meanings and skeleton keys. Ingenious and cryptological explanations have fallen out of favour, due to their own excesses, and Dylanology pursues more sober, empirical and encyclopaedic projects. What was valuable, however, even in such wild theories as A.J. Weberman’s, was their search for the ‘thread’ of Dylan’s work. Weberman’s ‘plot’, applied to Dylan’s career up to the early Seventies, was the story of a Revolution betrayed by its leader (as far as I can make it out). He supplied for the country music the cry of ‘Judas!’ that had earlier been flung at the rock. If we don’t find schemes like this – or Stephen Pickering’s interpretation of the poet’s progress in terms of the Cabala and Jewish mysticism – satisfying, it’s because they seem reductive. Tying the form of artistic creation to another, extrinsic form, they restrict rather than expand its scope.

The problem with approaching poetry or song as ‘code’ is that code in itself is meaningless. Once it has been deciphered it is ignored; it adds nothing more to the real message it was concealing. If a song is coded in this sense, then all our responses to what it ‘seems’ to be about would be like delusions. Hence our natural hostility to what is effectively a destructive form of interpretation. But a song can have ‘hidden’ or ‘other’ meanings in another way: not as concealed within it or ‘behind’ it, but hidden in the sense that we don’t see them until we see the larger form of which the thing we are looking at is a part. These are the relations that give a work of art its third dimension, its depth. The larger form is the artist’s body of work and also the “order of words” that Northrop Frye speaks of, the total form of literature.

With

Dylan, of course, we cannot say simply ‘literature’. One of

the reasons he strikes us as such an important figure is that an integral

view of his work has to place it simultaneously in both literature and

‘popular music’ (there’s no word as neat as ‘literature’

to describe this other field); and therefore he unites, or reunites, these

estranged relations. He’s not alone in doing this. Burns, Brecht

and Lorca are three who spring to mind as co-conspirators, but their work

has all ended up as books, and been subsumed into literature, and Dylan’s

will not be subsumed. In fact, at the moment the emphasis is the other

way, partly because of the nature of Dylan’s writing in its current

phase, and partly because that ‘other’ field – the golden

triangle that lies between points A (for art music like avant-garde jazz),

C (for commercial or chart music) and F (for the various shades of ‘folk’

music and field recordings) – is at present, thanks to CDs and expiring

copyrights, being formed into a canon of its own.

With

Dylan, of course, we cannot say simply ‘literature’. One of

the reasons he strikes us as such an important figure is that an integral

view of his work has to place it simultaneously in both literature and

‘popular music’ (there’s no word as neat as ‘literature’

to describe this other field); and therefore he unites, or reunites, these

estranged relations. He’s not alone in doing this. Burns, Brecht

and Lorca are three who spring to mind as co-conspirators, but their work

has all ended up as books, and been subsumed into literature, and Dylan’s

will not be subsumed. In fact, at the moment the emphasis is the other

way, partly because of the nature of Dylan’s writing in its current

phase, and partly because that ‘other’ field – the golden

triangle that lies between points A (for art music like avant-garde jazz),

C (for commercial or chart music) and F (for the various shades of ‘folk’

music and field recordings) – is at present, thanks to CDs and expiring

copyrights, being formed into a canon of its own.

In this respect Love and Theft is not ‘retro’ at all, because it’s encyclopaedia of ‘thefts’ goes hand in hand with a whole new level of documentation of its sources. Reference-spotting can be illuminating, but it’s not the end of hearing Dylan’s music in an integrated way – and it may not even be the beginning. Let’s say that the 12 songs of Love and Theft allude to 100 other records (it’s probably not an overestimate): we don’t necessarily get farther into it even if we track down every last one of them. The important thing would be to listen back and forth, so to speak. To know the why of one reference will tell us more than to know that 99 others exist.

Which brings me back to my Tarot reference. The point is not that ‘To Ramona’ is really about a playing card instead of a person, or that Bob Dylan once practised divination. The point is that the High Priestess helps us see the ground on which Ramona moves, a harmony to her melody, if you like. A further quote from Northrop Frye, from Fearful Symmetry, may suggest how John Donne and Woody Guthrie, Tarot and “corpse evangelists”, ‘To Ramona’ and ‘Chimes of Freedom’ all come to combine in the form we know as Another Side. Speaking of the Renaissance humanists, he points out: “They had in common a dislike of the scholastic philosophy in which religion had got itself entangled, and most of them upheld, for religion as well as for literature, imaginative interpretation against argument, the visions of Plato against the logic of Aristotle, the Word of God against the reason of man.” He goes on to say: “The doctrine of the Word of God explains the interest of so many of the humanists, not only in Biblical scholarship and translation, but in occult sciences. Cabbalism, for instance, was a source of new imaginative interpretations of the Bible. Other branches of occultism, including alchemy, also provided complex and synthetic conceptions which could be employed to understand the central form of Christianity as a vision rather than a doctrine or ritual…”

It remains only to say that in Dylan’s case the matter of references and possible allusions is slightly complicated by that aspect of him that plays the Riddler or the Jokerman. ‘Rainy Day Women #12 & 35’, anyone? Well, 1, 2, 3, 5 are the first four prime numbers, and the next in the sequence is 7, and this is the first track on Dylan’s seventh album. I’ve also speculated that they’re the numbers of hexagrams in the I Ching – something else he’s known to have been interested in, and once refers to openly: “I threw the I Ching yesterday, it said there’d be some thunder at the well.” An interesting reading in the light of Blood on the Tracks, though ambiguously put. I’d assume it was hexagram 51, Thunder, moving to hexagram 48, The Well, but it could be the other way round. Either way, the judgment on The Well is fitting for that fresh tapping of former powers: “The town may be changed, but the well cannot be changed. It neither decreases nor increases…” And the Thunder of the I Ching, as described in the translator Richard Wilhelm’s commentary – “A yang line develops below two yin lines and presses upward forcibly… It is symbolised by thunder, which bursts forth from the earth” – is something that might well be called Planet Waves.

So to return to Nos 12 and 35 – hexagram 12 is Standstill or Stagnation, and Blonde on Blonde is all about stasis and stuckness. Richard Wilhelm comments: “This hexagram is linked with the seventh month… when the year has passed its zenith and autumnal decay is setting in.” That seventh album again, and according to my seasonal arrangement of Dylan’s records, Blonde on Blonde is an autumnal work. And 35? That’s called Progress and the image is of the sun rising over the earth. What lies beyond the stasis of Blonde on Blonde is, whaddyaknow, a New Morning.

These are plausible references for the numbers, if you think they are there for any reason. They’re also both biblically important. Twelve, as in tribes and apostles, and 35 as a number of the apocalyptic proportion, as stated in the formula of Revelation, “a time, and times, and half a time”, i.e. 1 of any unit, plus 2 of it, plus a half = 3.5 and any of its multiples, like 7, or 70, or 35. The formula occurs, in fact, in chapter 12 of Revelation: “And to the woman were given two wings of a great eagle, that she might fly into the wilderness, into her place, where she is nourished for a time, and times, and half a time, from the face of the serpent. And the serpent cast out of his mouth water as a flood after the woman, that he might cause her to be carried away of the flood.” (‘Rainy Day Women’, anyone?) “And the earth helped the woman, and the earth opened her mouth, and swallowed up the flood which the dragon cast out of his mouth. And the dragon was wroth with the woman, and went to make war with the remnant of her seed, which keep the commandments of God, and have the testimony of Jesus Christ.” (“They’ll stone ya when you’re tryin’ to be so good” anyone?)

Yet the suspicion is strong that they could actually be any numbers, and that what they mean at the beginning of the record, attached so arbitrarily to a title so arbitrarily attached to its song, is: prepare to be baffled. And yet, and still – why those particular numbers? Follow the Riddler into the labyrinth, but let a thread unwind as you go, or you may end up lost in there. A final quote from Northrop Frye. Of Blake he says: “He is not writing for a tired pedant who feels merely badgered by difficulty: he is writing for enthusiasts of poetry who, like the readers of mystery stories, enjoy sitting up nights trying to find out what the mystery is.”

Home | Books | Music | Events | New work | Contact & ordering